The Hypaspist Corps: one Identity, three units, and many functions.

by

Dr Manousos E. Kambouris, member

of Association KORYVANTES

THE HYPASPIST CORPS – Article on ANCIENT WARFARE MAGAZINE (Issue IX.5, November 2015)

The elite Hypaspist Corps (Υπασπιστές) was a special unit, inherited by Alexander along with the other components of the Macedonian army. The paramount importance of these troops not only during the great battles of Philip and Alexander, but in almost every clash during the campaign of the latter, ignited the interest and curiosity of many scholars.

Though, the absence of contemporary literature, the huge time gap from the facts to our most reliable source, Arrian’s Anabasis (aprox 500 years later), the shady descriptions of Arrian and the frequent reorganizations and restructures of the Macedonian army under Alexander have caused extremely diverse opinions. Although the unit was renamed to Argyraspides and, most probably, re-oriented towards strictly line infantry operations (retaining an elite status but not its former special-warfare status), its functions and internal organization are rather straightforward before this restructure. We are to try to present a logical answer to the problem which caused a disagreement between Profs. Hammond (Ancient History Bulletin 11.1 /1997) and Bosworth (Ancient History Bulletin 11.2-3 /1997), i.e. whether there were one or two special infantry units in the Macedonian army, functioning in the role the Napoleonic Era’s Guard units were. To tackle this problem we also find ourselves committed to cope with the problem of the organization of the Hypaspist Corps and of the Bodyguard unit(s) existent within the Macedonian army. The references, unless otherwise specified, mention Arrian’s Anabasis Alexandri.

Experimental reconstruction of an Macedonian Hypaspist / Royal Guard Officer of the Seleucid Kingdom. The reconstruction has been extensivelly presented in magazine «ANCIENT WARFARE MAGAZINE» (issue VIII.4). The Officer carries a composite leather-thorax – reinforced with metal scales on the right side – a heavy slashing ‘Kopis’ and an Attic-type helmet. The stars of the Macedonian Dynasty symbols fitted on the epomis (epaulets), may declare the warrior’s Macedonian heritage. This armor could be a typical sample of relevant units of the Hellenistic armies. Armor construction by Hellenicarmors. Foto by Andreas Smaragdis. Image courtesy of KORYVANTES Association.

There are some basic things to remember when dealing with this elite unit, the Hypaspists:

First, when Philip ascended to the throne, the unit had been at first some 500 strong. It expanded till we find it 3,000 strong during the campaign of Alexander (‘three chiliarcies’, V.23, 7).

Secondly, the name of the unit means shield-bearerss and in such strength they should be associated (loosely?) with the Companion (Εταίροι) cavalry – at the beginning just 600 strong. Before detached from them and reformed as a unit per se, these men might well follow the cavalrymen, carrying the heavy shield of the Companions. Not only has this been a practice well-followed by southern Greek Hoplite troops, but half of the Companions were specifically ordered by Alexander in one instance to “take on their shields, dismount and charge on foot mixed with the other, mounted half” (I.6, 5). This means that they had shields (for cases where they had to fight on foot, i.e. sieges), which were not carried when fighting mounted. One cannot refrain from an association with the Hoplite-type shield found by Prof. Andronicos in Vergina, which would stand well to such a task for its royal owner.

The core of the Hypaspists might have once been the followers of the Companions, following their masters in battle (perhaps in the like of the southern hamippoi) and carrying their shields – at least in forced marches. From this point to their using the shield in battle, when their master has no use for it fighting mounted, the distance is rather short. To further enhance this view, Arrian himself specifically talks about the Companions’ Hypaspists under Nicanor in I. 14,2 referring rather to the whole of the corps. This corps might well be a standing army, (at least since Philip reorganized it to a special, independent unit) very much to the like of southern Epilektoi (Arcadian Eparitoi) units which first appeared in Argos in 418BC (1000-strong) and then spread out to many states ant confederacies. Such a relationship could also make their training to Hoplite tactics (in-phalanx and the new skirmishing and mobile kind of Hoplite warfare of the 4th century BC) much more probable and explicable. One must not forget the coincidence of size between Hypaspists’ Chiliarchies and southern Hoplite units as the Athenian Taxeis and the Laconian Lochoi (during the 480-479 BC period), both being 1,000-strong.

During Alexander’s reign, we understand a 3,000 strong corps (V. 23,7). One may suppose that the first step would have been from the first 500 to 1,000 and then to 3,000. After all, during these days, the Companion strength was 200 (accounting for the Royal Squadron – maybe 300 strong – the 6 first-line squadrons of the campaign and the second-line squadrons left to Antipater, each at a strength of 150 cavalrymen [1]) from the original 600, a 350% increase.

Tetradrachm from the Seleucid era (305-295 BC) under the reign of Seleucus Nicator. In left side it depicts Alexander the Great wearing an open horned Attic-type helmet covered with panther skin. On the other side it depicts Goddess Nike (Victory) crowning a trophy triumph. In the depicted panoply we can observe the anatomical muscled-cuirass, the “pteryges” and the hollow hoplon-type shield with the symbol of the star of the Macedonian dynasty. Image may be copyrighted.

Thirdly, during Alexander’s campaign we hear of missions assigned to detachments of 500 and 1000 Hypaspists (III. 29,7), which are rather logically whole units of the corps. This biadic organization differs from the Foot Companion Taxeis, 1,500 strong each and consisting of three 512-troop units or six 256-troop Syntagmata (the term for the latter might also have been Lochoi). But under the tactical level (Taxis and Chiliarchy) it may well be common, the Hypaspists being arrayed in files of eight when fighting as phalanx, like most southern Hoplites. The organization would well be biadic to both line infantry corpses up to 500 men, and from then on the Hypaspists retained the biadic organization to the tactical level (1000-strong units) whereas the Foot Companions changed to triadic organization in tactical level (1,500-strong Taxis, which allows for an independent infantry line with two kerata and one center.

So, for the one and whole Hypaspist Corps we must assume either two 1500-strong units, or three 1,000- strong units. With commanders’ name like Hiliarches (I. 22,7 [2]) I would opt for the second alternative, for one more reason: This division is much more suitable for the kind of mobile medium infantry these men were. Three units offer more tactical combinations and flexibility and 1,000 men are easier to command in mobile operations than 1,500 (that poses no problem for the Foot Companions, for, despite oftenly used for operations in uneven ground, they were primarily line infantry and not elite/special infantry). After all, in III. 29,7 and in IV 23,7 we specifically read about one and three Chiliarchies respectively.

So, starting from the beginning, first there was the unit of the Companions’ Hypaspists, 500-strong, detached from the Companion Cavalry. Though, their name in an army full of esprit-de-corps and special units (the simple line infantry was given the prestigious name Foot Companions / Pezetairoi) was associating with their ante-detachment status. This same unit must have been originally doubled to 1,000 by Philip (maybe concurrently to the doubling of the Companion cavalry force). When the second Chiliarchy joined in, once more doubling the strength, it probably got another name, despite joining the very same Hypaspist Corps. Possibly this name was Vasilikoi Hypaspistes (Royal Hypaspists) [3] to emphasize the difference in origin from the more senior Chiliarchy. These men (Royal Hypaspists) were not coming from any kind of association with the Companion noble cavalry. The third unit of the corps was the Agema (though one can’t be sure on the seniority of the three Chiliarchies, which might well not be associated directly to their year of establishment; perhaps troopers that excelled in the two first Chiliarchies, were honorably promoted to joining the Agema).

Now, to how the recruiting basis of these three units has been differentiated, I can offer no further ideas. Though, the whole corps must have been recruited from the whole of Macedonia, instead of the territory-based recruitment of the Foot Companion Taxeis. That would well explain the sporadic use of Macedonon Agema, by meaning “the best among the Macedonians”. [4]

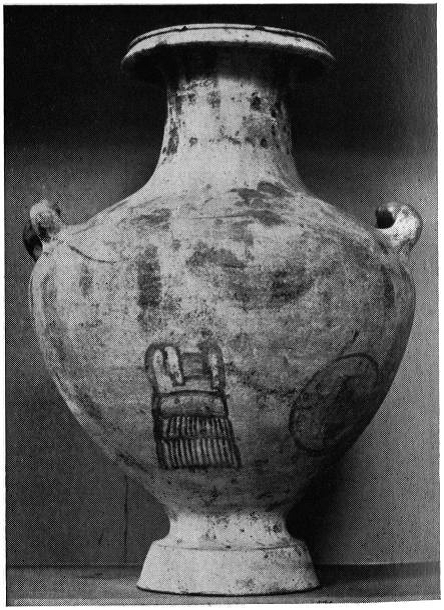

The Hellenistic Military tradition preserved on the early Christian centuries through religious syncretism. The Greco-Egyptian god-warrior “Heron”, a deity which it’s cult dates back to the Ptolemaic era, with halo and military uniform. Remarkably , many centuries after the overthrow of the Hellenistic kingdoms, in the Roman Egypt the God “Heron” is depicted bearing a Hellenistic “tube and yoke” cuirass with scales, double row of long “pteryges” and a gorgoneion patch on the chest, reflecting the typical form of an officer of the Hellenistic Armies. Source : Ernst H. Kantorowicz, “Gods in Uniform” , Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 105, No. 4 (Aug. 15, 1961), p369. Image may be copyrighted.

The other important aspect on the subject is the use of the corps in battle. Arrian may refer in different words to the Agema, sometimes just Agema, other times as Royal Agema and even Macedonon Agema. But he is rather cautious – let’s not forget that he writes half a millenium later – to the use of “the rest of Hypaspists” and the Royal Hypaspists. He confuses only twice these two terms, in Thebes (I. 8, 3-4) and in IV. 24, 10 (we will focus on these cases later). This really should make us think that there were three, distinctively named Chiliarchies which comprise the corps. Alternatively, one might think that one pentacosiarchia’is the Agema, another is the Royal Hypaspists and the remaining four are «the rest of Hypaspists». For the latter view, neither anything for nor against appears in the text, but the indirect contrary testimony of the battle outside Thebes and also V. 13, 4, for which more later on.

The Nicanor’s Command really seems to comprise only two units in some cases, Gaugamela being one of them, as Prof. Bosworth rightly points out (other is Issus, II. 8,3). This is to prove nothing – even today when need arise, a battalion or brigade can be detached from the regiment/division it belongs to (organically) and be put somewhere else, maybe under a different command or by itself. This must well have been the case in Gaugamela. As to where this third Chiliarchy is to be searched for, we do not think that the camp is where an elite regiment would have been left by Alexander during the battle, which entailed the Mastery of Western Asia.

Moreover, in the very same battle, the first-line heavy infantry of Alexander looks like comprising only 9000 Foot Companions plus two or three thousand Hypaspists (III. 11,9). This is far below the maximum, in a battle where Alexander possessed some 47,000 troops (III. 12, 5). The difference can not be due only to light infantry and Cavalry. The latter is estimated in 7,000 by Arrian himself (III. 12, 5); thus leaving some 28,000 of uncommitted troops, a little too many for guards in the camp and flanking guards, where Arrian explicitly states that the light foot has been posted (III. 12, 2-5). The solution comes from some very dark parts of the text. Arrian speaks (III. 11,1 and III. 14,6) of phalanga amphistomon (double edged phalanx) and “hegemosi ton epitetegmenon” (commanders of the rear troops). He distributes the lack of resistance in the Macedonian camp to the fact that nobody in there expected enemy cavalry cutting through the «double phalanx» (III. 14,5).

These all should lead to the conclusion that there was indeed a second line of heavy infantry, exactly behind the fist line (Macedonian phalanx). This second line must have been distributed to commands, each covering equal space with the Foot Companion taxis to which it is attached. It was to follow the movements of the front command (so the delay of one taxis, that of Simmias, caused a breach to both the lines-III. 14,4-6) but to a distance in its rear. This distance permitted, as Alexander ordered –and as happened indeed- to the rear units, uncommitted frontally, to turn back and cope with any danger at the army’s rear (III. 12,1 and III. 14,6) while at the same time the front units (Foot Companion Taxeis) were engaging undisturbed the Persian line frontally. This scheme is somewhat reminiscent of the Roman anterior-posterior centuries per maniple, with two basic differences: First, the rear units do not belong organically to the front units’ command – they have been arranged for the battle under their command. And secondly, they are not to take a place next to the front line units to form a solid line, because the front line by itself should have been solid. This explains why the rear command of Simmias did not move forward to close the gap. The orders would have been to protect the rear at any cost. In this way, Alexander could have protected the rear of his phalanx to remain not only safe, but also unhindered to shatter the Persian line in its front (III. 14,3).

Cinenary urn of a warrior of the Ptolemaic Egypt. We can observe the “tube and yoke” cuirass and the big hoplon-type shield. Source : Notes on Supplementary Plates CCXLVIII-CCLI, Greece & Rome, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Oct., 1966), p264. Image may be copyrighted.

The very popular thought, that the units (Taxeis) of the phalanx turned (onto their rear halves) backwards is, to our idea, unacceptable for two reasons: First, turning half the ranks means diminishing in half the weight of the charge. Second, it presupposes a roman-like organization of the units; that is that the second-in command of each Syntagma been placed in the second half of the rightwards file and commanding the rear half of al the width of the Syntagma. This made sense in the roman army, where the rear half (century) of the unit (maniple) was moving as an entity to the front line, next to the front half (century). But in the Greek armies (Alexander’s army being an evolution of them), every rear half-file was assuming position next to its front half- file. So the rear half of a unit was no separate entity, so as to assume initiative and be ordered by a commander to face back. This would require the unit’s leader, already engaged in the front-to front fight in the case of Gaugamela, to issue orders for the half- files and half-file leaders to face about, which is both impractical and in contrast to the passage, which speaks for rear commanders being tasked to reverse and stand. Just as a reminiscent, we mention that the second-in-command in each Syntagma was posted in the front line also, exactly in the middle of the first row (which is practically the right edge of a half-regiment’s files), since the division of the command was made by grouping together the files and not the rows.

If this double line is accepted, there is absolutely no problem where to look for the third Hypaspist chiliarchy. It must have been placed to the right edge of the second line, behind the two Chiliarchies found in the front. The inconsistency in numbers (2 in front-one in the back) could well have been remedied by the rear unit being deployed in half the front one’s depth, solution which, if taken for all the infantry deployment, meant a 2:1 distribution of manpower in favor of the first line; this adds to the ferocity of the charge. This would lead to a 11,000 strong first line (2 Chiliarchies of Hypaspists and 6 Taxeis of 1,500 Foot Companions each) and a 5,500-strong second line (half of the first), that is 16,500 heavy infantry, a far more believable number, which allows for enough manpower distributed to guards’ duties in the two camps and flank protection. We must not forget that behind the phalanx, there were squires (grooms), who “arrested” the Persian-Scythed chariots which made their way through the corridors the phalanx opened when faced with their onslaught (III. 13,6). Needless to say that the division of the rear line to units closely attached and following the Taxeis of the first line permitted the opening of these corridors with excellent efficiency (compared to the capabilities offered by a possible “monoblock” command of the rear line). Moreover, in that same part (III. 13,6) Arrian specifically mentions the Royal Hypaspists along with the grooms arresting the chariots that had passed harmlessly through the phalanx to its rear. So, Royal Hypaspists (not Companions’ Hypaspists, the Agema neither) were in such a position as to operate in the rear of the double-edged phalanx. This intrigues us to think that Nicanor’s immediate command comprised all three Hypaspists’ Chiliarchies, in a very modern two-in front-one in the rear- arrangement. No matter how enterprising Alexander had been, this is rather unlikely, as such arrangements were not heard off at that time, and also since at that battle, as we said, the rear units had their own commanders (III. 14,6).

Moreover, Diodorus (XVII. 58, 3-4) says that the phalanx produced noise to terrify the horses of the Scythed chariots by striking the shield against the sarissas. This is difficult to imagine. Contrary to that, this kind of “sound-weapon” was used by Hoplites (Xenophon describes it in his Anabasis) and it would be very easy for the allied Greek Hoplites, posted behind the Foot Companions’ Taxeis to do so with their Hoplite shield and spears.

Another issue is the battle outside Thebes. I must disagree with Prof. Bosworth’s view, that the second Macedonian infantry line might be the whole (of the rest of) the phalanx. Indeed, the engagement of two Taxeis left 4 more uncommitted. But the breach to the Theban defensive position can’t have allowed for more that 2 Taxeis’ deployment – otherwise, the remaining Taxeis would have taken their flanks from the very beginning – not to speak about cavalry. The very nature and positioning of the stockade and trench must have hampered deployment, even when breached, so Alexander should not have been able to deploy his line infantry to this width – even outside the trenches. He must have been restricted to a similar number of men, at least if he was to use them in some effect. The 2 Taxeis numbered 3,000 men altogether. The two mentioned Chiliarchies, (Royal) Hypaspists and Agema numbered only 2,000, which allowed for either a thinner and more manageable line, or a less dense line to permit the fleeing units passing through the line to retire. This retirement through the second line (in files and not in whole units, as was the roman manipular system) could explain Diodorus’ account (Diod. Book XVII. 11,1-12,4) of the Thebans’ receiving two Macedonian attack lines before breaking. One can imagine that the third part of the army (Diod. Book XVII. 11,1) would comprise of the rest of the Taxeis of Foot Companions and the rest of Hypaspists (one chiliarchy) –that is if indeed the second line comprised only two Chiliarchies.

Hellenistic (late 4th century BC) anatomical muscled-cuirass, with open helmet of the Attic-type, currently been exposed in the Getty Museum (USA). The thickness of the muscled-cuirass is 0.535 m and the helmet is 0.225 m, while there is no record of where those items have been found. Source : Emeline Hill Richardson, The Muscle Cuirass in Etruria and Southern Italy: Votive Bronzes, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 100, No. 1 (Jan., 1996), p93. Image may be copyrighted.

The problem is that this is one of the very few (just two) parts where Arrian mixes Royal Hypaspists and the rest of the Hypaspists. In I. 8,3 he mentions the latter being posted next to the Agema while in I. 8,4, that is just some lines later, he mentions that the fleeing Foot Companions where received by the Agema and the Royal Hypaspists. This could well mean that in this case all three Chiliarchies were lined up, in all 3,000 men, exactly as many as the first line of two 1,500-strong Taxeis comprised. Due to ground factors, the retreating Foot Companions might have well retired through the two of the three lined Hypaspist Chiliarchies.

It remains a –highly unlikely to us-possibility that in each of these two engagements (Gaugamela and Thebes), a Chiliarchy of Hypaspists might remain attached to the companion Cavalry, as originally was the case.

I also would like to mention that the edition of Arrian I have (Arrian Anabasis Alexandri, Harvard Univ. Press) doesn’t have Agemata (plural) in the text in the Thebes’ battle (I 8,3-4) – though footnote 5 tackles this point. In any case, placing cavalry in such proximity to trenches and uneven ground doesn’t sound a very sound move to me for a commander like Alexander.

The other part where Royal Hypaspists are thought to refer to the whole Hypaspist Corps, is IV. 24, 10. There, Arrian says that the third of the Royal Hypaspists was dispatched to a certain task. Many think that this means the third of the Hypaspist Corps, i.e. 1,000 Hypaspists. Things might be a little more complicated. Arrian uses in other contexts (III. 29, 7) the word Chiliarchy for a 1000-strong unit of the Hypaspists assigned a task. In this case, since they were put under a different tactical command, along with other troops, they most probably were sent as a unit and not as selected individuals (which is the case in other specific missions, as when getting ready for a naval engagement out of Tyros, when the most able to the task were selected). So it may well be, for Arrian not talking about a Chiliarchy, that in fact the detachment was not a chiliarchy and was indeed the third of the Royal Hypaspists and not the third of the Hypaspist Corps. So, in this case (IV. 24, 10) maybe Arrian is very accurate and it is our understanding that must bear the blame.

The passage about Hydaspes (V. 13, 4) which is mentioned by Prof. Bosworth simply verifies this opinion. All three Chiliarchies are mentioned one by one, and we also learn of another commander, Seleucus. Could he have been in charge of the Royal Hypaspists in Gaugamela as well or is he replacing Nicanor as commander of the corps? This passage speaks about Royal Hypaspists under Seleucus, Agema and then the rest of Hypaspists being arrayed according to the order of the day. This implies more than one separately commanded units except the two already mentioned. So, he could well be speaking about 500-strong units of the corps, of which there were 6 (coupled in 3 Chiliarchies). This is the only part of Arrian’s account that could let us believe that Royal Hypapsists and Agema are rather 500-strong units of the Hypaspist Corps and not full Chiliarchies.

This leaves some more questions open, about Arrian’s style. Prof. Bosworth rightly points out that there’s only one mention of Macedonon Agema and numerous of Agema and Hypaspists’ Agema, plus Royal Agema. The same goes with the third Chiliarchy of the Hypaspists and the corps. In Granicus we hear of Companions’ Hypaspists (I. 14, 2), and from then on usually Hypaspists. As far as the Agema is concerned, I think that clearly mentioning Hypaspists’ Agema Arrian is to remind to his reader that this Agema unit is part of the Hypaspist Corps [5].

But from this point on, there are two distinct possibilities:

- The full name of the Agema was indeed Macedonon Agema and once mentioned, to inform the reader about the full name, Arrian shifts to the simpler word Agema, from time to time reminding that it is a Hypaspist Unit.

- The name of the unit is simply Agema. This leads Arrian to define, just once, that it is a Macedonian unit (and most probably recruited from the whole of the state) not to allow any confusion with the Agema of the Spartan army (which must have been the prototype) or any other Greek army which had such a unit.

As far as the Companions’ Hypaspists are concerned, the solution might well be a similar one. Arrian mentions this name just once because he doesn’t know which of the following might be correct:

First alternative, the whole Hypaspist Corps is called Hypaspists and comprise three Chiliarchies: Agema, Royal Hypaspists and Companions’ Hypaspists, the latter being the first unit of the corps to be formed. Second alternative: The originally formed unit was Companion’s Hypaspists (to this attests I. 14,2) but when the corps expanded, this title described the whole corps, the original unit being thus called simply Hypaspists and being only the third of the corps, along with the Royal Hypaspists and Agema. This Chiliarchy, Hypaspists (ex Companions’ Hypaspists) Arrian refers to as «the rest of the Hypaspists» for lack of a suitable and accurate characterization or epithet.

Speaking about the polymorphism in Arrian’s language, which is a central argument of Prof. Bosworth’s account about the Guard Units of the Macedonian army, I have to bring forward that this could have been the case if the author had not also written a tactical treatise, where terms are used strictly and systematically. In other words, Arrian might be expected to use such linguistic behavior in every part of his narrative BUT the military terminology. That for no reason means he is always accurate. He has a hazy comprehension in many parts and at the crossing of Hydaspes he puts half of the Hypaspists on the same little triakondoros with Alexander (V. 13, 1).

I also have to disagree with Prof. Bosworth’s view of Somatophylakes (Bodyguards) and Vasilikoi Somatophylakes (Royal Bodyguards) being the one and only. There were only 7 Bodyguards and an eighth was added; Peucestas, as an honor for saving Alexander’s life in Malli. I cannot argue either for or against Prof Bosworth’s view of them belonging to the Companions, but Peucestas must have been a Hypaspist [6]. On the other hand the Royal Bodyguard is stated to follow Alexander himself in a special mission, against the Uxians, along with some Hypaspists and «8,000 of the other infantry» (III. 17,2). This means that the Royal Bodyguards was a unit by itself, for there would have been no reason for Arrian to enumerate just seen bodyguards along with other units (Hypaspists and other types of infantry). This Royal Bodyguard must be some hundred strong and be able to assume battlefield assignments, much like the Guard units of Napoleonic Era.

Moreover, in IV.30,3 Arrian states that Alexander took the «Bodyguards and Hypaspists up to 700″ to occupy the Rock, abandoned by its defenders. This readily reads as a unit of Hypaspists (500, since their major unit was the thousand – Chiliarchy and the Macedonian military organization was basically binary) and the Bodyguards (700-500=200). However, its primary function would have been – understandably and again like European Renaissance Guard units) to attend a variety of duties (such as the guarding of the palace in peacetime or whenever the king resided in one – not to mention secret police/military police functions). I must admit I have not been able to question Prof. Bosworth’s remark that Ptolemy is once referred to as Bodyguard and some lines afterwards as Royal Bodyguard. He lead a counterattack of two Taxeis plus light troops in action, and the only thing that could reconcile these two different functions is the possibility of him holding a command or rank also within the Royal Bodyguard.

References

[1] In II. 9,4 Arrian specifies 300 cavalrymen as a precaution in Issus, for the Persian troops in the hills, whereas a little earlier had named two Ilai of the companion cavalry being tasked to this, which leads that each squadron-ile was 300:2 = 150 strong.

[2] Addeus was his name and is mentioned as a casualty, along with the Toxarches – leader of the archers. Arrian here makes a careful distinction. Usually he speaks of “archers’ chiliarch”, since they numbered one chiliarchy but in here he changes the term to distinguish from another chiliarch. Since for the light troops, like javelineers (mostly allied Greeks and Thracians) he refers to Hegemons, and the term Chiliarchy is used only for macedonian army proper units and for the archers, which were a mix of macedonian and non-macedonian –at the beginning Cretan- ones (IV. 24, 10), we should rather conclude that Addeus was a chiliarch of Hypaspists.

[3] “Vasilikoi” in Greek may well mean, in diferent contexts: “Royal”, “belobging to the king”, “Kingly”, “King-like”, “Royalist”, “worthy of a King”.

[4] Since joining by virtue and enrolled by the whole of Macedon

[5] I could also be very bold to propose that Agema proper was a chiliarchy and comprised two pentacosiarchies, Makedonon Agema and Royal Agema. This would explain the plural of Agemata outside Thebes in I. 8,3.

[6] In I. 11,8 Arrian says that the sacred arms taked from Troy were born by the Hypaspists before Alexander in battles, and in VI. 28, 3-4 Peucestas is supposed to have assisted Alexander in Malli citadel bearing the shield taken from Troy, which makes him very probably a Hypaspist. Moreover in VI. 9,4 Arrian specifically states that the Hypaspists were following Alexander in his assault to the walls and moreover, Diodorus in XVII. 99,4 calls Peucasta a Hypaspist.

Copyright of KORYVANTES Association – do not copy or reproduce without permission