by Spyros Bakas, Archaeological Institute of the University of Warsaw

Τhe complete version of this study will be published in the upcoming Volume IV of the Archaeological Journal «Syndesmoi», University of Catania / Italy

the study is dedicated to my archery – instructor Mr Kostas Papantoniou

Introduction

Archery had a dominant role in Bronze Age, especially in later period. The technological evolution from the self bows to the composites was a significant factor that affected the Warfare in several ways. Composite’s critical advantage was that they can be made smaller because they retain their strength through the correlation of different materials (wood, sinew, horn). They had more strength, far more range and their small size results in more mobility than the self bows [1].

The first depiction of a probable composite bow lays in the victory stele of Naram-Sin of Akkad (23rd century BC) [2]. It was introduced into Egypt by the Hyksos in the 18th century. The earliest example of a composite bow was found in the tomb of Ahmose Penhant (16th century BC) [3] while thirty-two more have been found in the tomb of Tutankhamen [4]. However we do not have any archaeological examples from the Aegean Bronze Age world. This brief study will try to approach the issue of the use of composite bows in the Minoan and Mycenaean Warfare attempting to include all the possible archaeological iconographical and textual evidence that could support this argument.

Archaeological Evidence

Bekroulaki et all. suggests that a bow in a wall painting in the palace of Nestor at Pylos could possibly be a composite one, due to the white layers of paint [5]. A bead-seal from Thisbe shows a goddess as Britomartis or Diktynna hunting a stag. As Evans notes, the appearance of thongs that cross the bow at intervals indicates that it is of the composite or Asiatic kind [6]. Evans also mentions a gold seal belonging to the same treasure, depicting two combatants with small composite bows [7]. An archery thumb ring found in the area of the Mycenaean Citadel and dated to the late Bronze Age [8] indicates that it could be used along with a composite bow –probably by a chariot archer. One of the signs of the Phaistos disc represents an unstrung bow with recurved limbs and straight grip [9] which Evans defines as “Asiatic Composite” [10].

There is a large number of smiths in Pylos tablets. These are aligned with the bureaucratic and centralized structure of the Mycenaean palatial centers. The word “to-ko-so-wo-ko“ [11] which appears five times in the tablets, refers to the profession of the “bow-maker” (τοξοφοργός/ toksoworgos). Furthermore, the word “ke-ra-e-we“ is been translated as “worker in horn” [12]. In the tablets we find evidence for the use of horn in the production of furniture, wheels, bridles and weapons [13]. There is no evidence, however, for the use of horn in the production of bows.

Nevertheless the word reminds us the maker of the bow of Pandarus who was “a worker in horn” (κεραοξόος τέκτων) [14]. These professions indicate a specialization that could be associated (even indirectly) with the construction of the composite bows. Based on the evidence from the Pylos “chariot –tablets” we do know that this Palatial centre could field hundreds of chariots [15] while also there is a record that there are 6010 arrows stored in this particular place [16]. Apparently those large numbers of chariots and arrows support the need for military arming. So, it seems more likely that the Palatial centers would need those “bow makers” mostly for military purposes rather than just for hunting. Therefore, the construction of composite bows – as weapons of the Mycenaean aristocrats – seems to be the most possible occupation of those craftsmen.

Homeric Elite Bowmen

In Homeric epics there are two bows that are described to be of composite structure. The bow of Pandarus was made of the horns of a wild goat [17]. This when it is fully drawn it is noted as “κυκλοτερές” [18] (circular). This adjective supports the argument that its structure is composite, as only the well-made composite bows can sustain a very high degree of curvature, while bows of simple structure would break under the strain involved in such extreme bending [19]. Odysseus is presented to provide a special treatment to his bow under fire [20] in order to render it more supple and amenable. It seems that the horn needed to be softened and the sinews needed to be rendered fully elastic in order for the bow to be functional.

Odysseus examines the weapon carefully to make sure that it has not been gnawed by wood-warms called “ίπες” [21] (“ips”). This is confirmed by modern zoologists as a genus of Scolytidae beatles is also called “ips”. Those worms would have infested the wooden part of the bow and, on reaching maturity, have made their way out through the horn [22]. His bow is also described as recurved [23], curved [24] and sinuous [25] when unstrung. These descriptions imply that this characteristic in the position of rest was a very marked feature. This backward curving of the bow is a feature peculiarly associated with composite bows [26]. Finally, both the bows of Pandarus and Odysseus are referred to be kept in bow-cases («εσύλα τόξον» [27],»γωρυτώ» [28]): a device that could carry a drawn bow. These are associated with composite bows which are able not to lose their power if being strung for a long time.

Scale and Plate Armor

Howard notes that “at least in the same period as the battles of Megido and Kadesh (15th -13th century BC), Mycenaean aristocrats were primarily chariot archers” [29]. He also notes that that the Mycenaean chariot-archer was using the composite bow as his prime ranged weapon [30]. Bronze Age Chariot-archers could not carry large shields as they needed both their hands to use their bows. Thus, they relied to body armor for protection.

The only type of functional armor, that provides suppleness and sufficient protection was the metallic scaled. The four bronze scales that have been found in the Aegean basin – in Uluburun shipwreck, in the Citadel house in Mycenae, in Tiryns and in the island of Salamina [31] – support the argument that the Mycenaean noble warriors were familiar with scale armor corselets. Even Homeric warriors such as Menelaos seem to wear some kind of scaled armor [32].

A series of experiments conducted by Tom Hulit proved that bronze scaled armor, even composite rawhide/bronze scaled armor proved to be extremely resistant to the Egyptian composite bow (39-44 lbs, 30’’-33’’) in shots of various types of arrows in the distance of 7 meters. Hulit concluded that the corselets managed to stop all the types of shots suggesting that this armor would have been suitable for use even in the most hazardous conditions justifying its high cost of production [33]. Such a body armor of high cost, combining high defense and constant mobility could be only associated with the characteristics of the composite bow: a noble and high cost weapon which provides strong shots against the elite chariot-archer opponents whilst also accords significant adaptability and readiness. Therefore, it is not dairy to conclude that the Mycenaean bronze scaled corselets would have been constructed for and against the composite bows. In the other hand heavy plate armor like the “Dendra” cuirass seem also to be designed to confront potent archery missiles. The cuirass comes from an era (15th century BC) where chariot archers where the primary threat and its bearer probably needed a full body protection against the enemy composite bows.

Minoan Horn Trade For The Egyptian Composite Bows

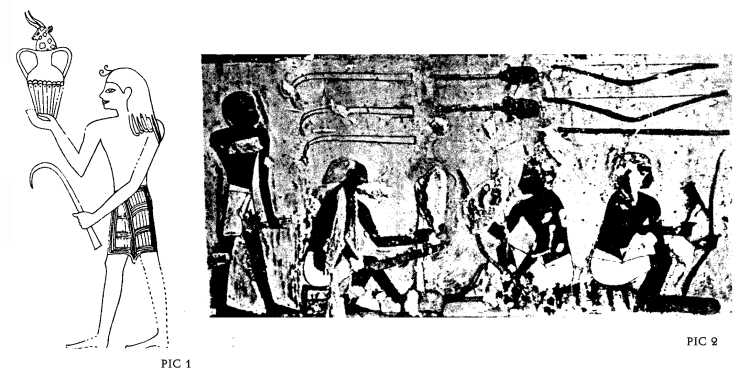

We do know that Minoans had close diplomatic and commerce connections with the Egypt at least from the early eighteen Dynasty period [34]. In a painting from the tomb of Menkheperreseneb, who was a noble in the era of Thutmose III (15th century BC), we see depictions of men in Aegean dress (obviously Minoans) bringing tribute or diplomatic gifts to the court. Two of those Minoans bearers bring objects identifiable as goat-horns. Similar horns are being portrayed in the “bowyers workshop” scenes in the same monument. In these scenes the bowers are presented to construct composite bows using six horns, worked by or ranged above them [35]. But why the Egyptians would value and appreciate such an item although the eastern Mediterranean basin and especially Egypt had large numbers of wild goats that could support the construction of composite bows? The answer could be retrieved by the fact that seventeen military campaigns were fought by the forces of Thutmose III during his reign [36]. Therefore, imported horns were required to match the large amount of bows needed to outfit huge armies for such campaigns.

Pic 1: “Foreign tribute scene” from the tomb of Menkheperreseneb with a Minoan bearing a goat-horn. (Watchman, S., Aegeans in Theban Tombs, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 20, Uitgeverij Peeters Leuven 1987, plate XXXVI )

Pic 2: Horns as they appear in the the scenes of “bowyers workshops” from the tomb of

Menkheperreseneb. (Watchman, S., Aegeans in Theban Tombs, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 20, Uitgeverij Peeters Leuven 1987, plate LIX )

Knossos Mc series tablets indicate that goat products including horn and possibly sinews were collected and stored in Knossos [37]. Apparently those products are associated with the Cretan wild goat – the “agrimi”– which was a symbol of masculine prowess and status in Minoan society. The Minoan palatial centers transported these goods to Egypt and – in exchange – the Minoan elites received prestige products, such as ivory and gold [38]. Nonetheless, the fact of commerce of horn and sinew to Egypt, implies a significant familiarization of the Minoans with the utilization of those items on the construction of local composite bows. It is attested through the Linear B tablets that Knossos could deploy 200 chariots – or even more – as archaeological evidence, such as the Phaistos disc sign, supports the evidence of the extensive use of the composite bow among the Minoan elites.

Conclussions

Bronze Age cultures valued the composite bow as a highly advanced and efficient weapon, offering solutions to both mobility and firepower in conflict. It is certain that the composite bow wasn’t commonplace in Minoan and Mycenaean world. It was a prestige item with high cost owned by the elite warriors and aristocrats. The weapon was in use by the Minoans probably from the early Neopalatial period and continued to play a dominant role in Aegean battlefields till the 13 century BC following the decline of chariot archery. Local wild goat horn -as a raw material- was in high value and extensive use by the Minoans during the later Neopalatial Period and we have enough indications to believe that Minoans were able to construct their own composite bows in a large scale. In the Mycenaean context a series of textual and archaeological evidence support the argument that the composite bows were constructed in a broaded basis by state’s specialist craftsmen at least till the end of 13th century BC while practically used till the end of Bronze Age.

References

[1] Zutterman, C. , The bow in the Ancient Near East. A re-evaluation of archery from the late 2nd Millennium to the end of the Achaemenid empire, Iranica Antiqua Vol XXXVIII, 2003, p. 122.

[2] Yadin, Y., The Art of Warfare in Biblical lands in the light of archaeological discovery, Weidenfeld and Nicolson publishing, London 1963, p. 47.

[3] McLeod, W.E., Egyptian Composite Bows in New York , American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 66, No. 1 (Jan., 1962), p. 136.

[4] Howard, D. , Bronze age military equipment, Pen and sword military publishing, 2011, . p29.

[5] Brecoulaki, H., C. Zaitoun, S. R. Stocker, J.L. Davis, A.G. Karydas, M.P. Colombini, U. Bartolucci, An Archer from the Palace of Nestor: A New Wall-Painting Fragment in the Chora Museum, Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens Vol. 77,No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 2008), p. 376.

[6] Evans, A, ‘The Ring of Nestor’: A Glimpse into the Minoan After-World and A Sepulchral Treasure ofGold Signet-Rings and Bead-Seals from Thisbê, Boeotia , The Journal of Hellenic Studies Vol. 45, Part 1 (1925), p. 22.

[7] Watchsmann, S. , Aegeans in Theban Tombs ,Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 20, Uitgeverij Peeters Leuven 1987, p. 89.

[8] Davis, A. Archery in Archaic Greece , Phd Thesis, University of Columbia, p. 11.

[9] Surnin, V. , Hieroglyphs of the Phaistos disc. History and full text translation, Volume I , Rostov on Don 2013, pp. 113-115.

[10] Evans, A, The palace of Minos. A comparative account of the successive stages of the Early Cretan civiliszation as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos. Volume 2, Part 1 Fresh lights on origins and external relations, Cambridge University press, New York 1928, p. 50.

[11] Heltzer, M., E. Lipinski, Society and economy in the eastern Mediterranean (c 1500 – 1000), Orientalia Lovaniensia Analekta 23, Uitgeverij Peeters Leuven 1988, p. 66.

[12] LUJÁN, E. R., A. BERNABÉ, Ivory and Horn Production in Mycenaean Texts [in:] Nosch, M-L., R. Laffineur (eds.), Kosmos. Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 13th International Aegean Conference/13e Rencontre égéenne internationale, University of Copenhagen, Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, 21-26 April 2010, AEGAEUM 33 (2012), p. 636. ,

[13] Ibidem, p. 627.

[14] «και τα μεν ασκήσας, κεραοοξόος ήραρε τέκτων» Homerus Epic: Ilias, Book 4, line 110.

[15] Chadwick, J. The Mycenean world, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1976, pp. 164-171.

[16] Drews, R, The end of Bronze Age” .Changes in Warfare and the catastrophe ca 1200BC, Princeton University Press, Princeton 1993, p. 124.

[17] “αυτίκ’εσύλα τόξον εύξοον ιξάλου αιγός αγρίου”. Homerus Epic: Ilias, Book 4, line 105.

[18] “νευρήν μεν μαζώ πέλασεν, τόξω δε σιδηρόν. αυτάρ επεί δη κυκλοτερές μέγα τόξον έτεινε” Homerus Epic: Ilias, Book 4, line 124.

[19] Balfour, H. ,The Archer’s Bow in the Homeric Poems, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Vol.51 (Jul. – Dec., 1921), pp. 302 -303.

[20] “Ευρύμαχος δ’ήδη τόξον μετά χερσίν ενώμα, θάλπων ένθα και ένθα σέλα πυρός”. Homerus Epic: Odyssea, Book 21, line 247.

[21] “εισορόων Οδυσήα. ο δ’ήδη τόξον ένωμα πάντη αναστρωφών , πειρώμενος ένθα και ένθα μη κέρα πες έδοιεν αποιχομένοιο άνακτος”. Homerus Epic: Odyssea, Book 21, line 395.

[22] Rose, J.H. , Odysseus’ Bow and the Scolytidae, Classical Philology Vol. 29, No. 4 (Oct., 1934), pp. 343-344.

[23] “ένθα δε τόξον κοίτο παλίντονον ΄ηδ φαρέτρη ιοδόκος, πολλοί δ’ένεσαν στονόεντες οιστοί”. Homerus Epic: Odyssea, Book 21, line 11.

[24] “αλλ’άγετ’ οινοχόος μέν επαρξάσθω δεπάεσσιν ,όφρα σπείσαντες καταθείομεν αγκύλα τόξα”, Homerus Epic: Odyssea, Book 21, line 263.

[25] “πη δή καμπύλα τόξα φέρεις, αμέγατε συβωτα”. Homerus Epic: Odyssea, Book 21, line 362.

[26] Balfour, H. ,The Archer’s Bow in the Homeric Poems, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Vol.51 (Jul. – Dec., 1921), p. 302.

[27] “Ως φατ’ Αθηναίη , τω δε φρένας άφρονι πείθεν, αυτίκ’εσύλα τόξον εύξοον ιξάλου αιγός ”. Homerus Epic: Ilias, Book 4 line 105

[28] “ένθεν ορεξαμένη από πασσάλου αίνυτο τόξον αυτώ γωρυτώ , ος ει περίκειτο φαεινός”. Homerus Epic: Odyssea, Book 21 line 54

[29] Howard, D. , Bronze age military equipment, Pen and sword military publishing, 2011, p. 57.

[30] Ibidem, p. 138.

[31] Ibidem, p. 74.

[32]

[33] Hulit, T.D. , Late Bronze Age scale armour in the Near East : an experimental investigation of materials, construction, and effectiveness, with a consideration of socio-economic implications, Department of Archaeology University of Durham ,Volume 1 of 1, Ph.D. Thesis 2002, pp. 123-133.

[34] Kelder, J, The Egyptian interest in Mycenaean Greece , Annual of Ex Oriente Lux (JEOL), 2010, p. 125.

[35] Watchsmann, S., Aegeans in Theban Tombs ,Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 20, Uitgeverij Peeters Leuven 1987, p. 90.

[36] Hussein, M.A. , Minoan Goat Hunting: Social Status and the Economics of War , Intercultural Contacts in the Ancient Mediterranean, Duistermaat , Regulski (eds.), OLA 202, 2011, p. 559.

[37] Ibidem, p. 567.

[38] Ibidem, p. 569.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Balfour, H. , The Archer’s Bow in the Homeric Poems, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland51 (Jul. – Dec., 1921)

- Brecoulaki, H., C. Zaitoun, S. R. Stocker, J.L. Davis, A.G. Karydas, M.P. Colombini, U. Bartolucci, An Archer from the Palace of Nestor: A New Wall-Painting Fragment in the Chora Museum, Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 77,No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 2008)

- Chadwick, J. The Mycenean world, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1976

- Davis, A. Archery in Archaic Greece , Phd Thesis, University of Columbia

- Drews, R, The end of Bronze Age” .Changes in Warfare and the catastrophe ca 1200BC, Princeton University Press, Princeton 1993

- Evans, A, The palace of Minos. A comparative account of the successive stages of the Early Cretan civiliszation as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos. Volume 2, Part 1 Fresh lights on origins and external relations, Cambridge University press, New York 1928

- Evans, A, ‘The Ring of Nestor’: A Glimpse into the Minoan After-World and A Sepulchral Treasure ofGold Signet-Rings and Bead-Seals from Thisbê, Boeotia , The Journal of Hellenic Studies 45, Part 1 (1925)

- Heltzer, M., E. Lipinski, Society and economy in the eastern Mediterranean (c 1500 – 1000), Orientalia Lovaniensia Analekta 23, Uitgeverij Peeters Leuven 1988

- Homerus Epic: Ilias

- Homerus Epic: Odyssea

- Howard, D. , Bronze age military equipment, Pen and sword military publishing, 2011

- Hulit, T.D. , Late Bronze Age scale armour in the Near East : an experimental investigation of materials, construction, and effectiveness, with a consideration of socio-economic implications, Department of Archaeology University of Durham ,Volume 1 of 1, Ph.D. Thesis 2002

- Hussein, M.A. , Minoan Goat Hunting: Social Status and the Economics of War , Intercultural Contacts in the Ancient Mediterranean, Duistermaat , Regulski (eds.), OLA 202, 2011

- Kelder, J, The Egyptian interest in Mycenaean Greece , Annual of Ex Oriente Lux (JEOL), 2010, p. 125.

- LUJÁN, E. R., BERNABÉ, Ivory and Horn Production in Mycenaean Texts [in:] Nosch, M-L., R. Laffineur (eds.), Kosmos. Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 13th International Aegean Conference/13e Rencontre égéenne internationale, University of Copenhagen, Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, 21-26 April 2010, AEGAEUM 33 (2012)

- McLeod, W.E., Egyptian Composite Bows in New York , American Journal of Archaeology 66, No. 1 (Jan., 1962)

- Rose, H. , Odysseus’ Bow and the Scolytidae, Classical Philology Vol. 29, No. 4 (Oct., 1934)

- Surnin, V. , Hieroglyphs of the Phaistos disc. History and full text translation, Volume I , Rostov on Don 2013

- Watchsmann, S. , Aegeans in Theban Tombs ,Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 20, Uitgeverij Peeters Leuven 1987

- Yadin, Y., The Art of Warfare in Biblical lands in the light of archaeological discovery, Weidenfeld and Nicolson publishing, London 1963

- Zutterman, C. , The bow in the Ancient Near East. A re-evaluation of archery from the late 2nd Millennium to the end of the Achaemenid empire, Iranica Antiqua Vol XXXVIII, 2003

Spyros Bakas is a postgraduate student of the Archaeological Institute of the University of Warsaw and member of the Association of Historical Studies KORYVANTES.

Copyright of KORYVANTES Association – do not copy or reproduce without permission